Last month finished the latest Berlin Biennale, developed under the curatorial concept “We don’t need another hero”, where the concepts of power that we drag from imperialism were questioned and where certain discussions were put on the map. The curatorial team was composed of five curators, among them the Brazilian Thiago de Paula Souza, who ends his contract in October of this year, who also asks “What does it mean to have a group of black curators if the institution is so white? What will happen to the issues that we are discussing now when we leave?”

By Carolina Martínez | Images courtesy Berlin Biennale & KW Institute for Contemporary Art

Carolina Martínez: The curatorial concept of the 10th Berlin Biennale “We don’t need another hero” questions the concept of power that we, unfortunately, drag from imperialism where the continents and countries colonized suffered in the most diverse ways and in all spheres of society. For instance, many adopted the power structures of the aggressors to subdue their own countrymen with promises of national identity and reconstruction. As part of the historical process of assimilation, the colonized took on the hero myth while the change emerged from the people. So the proposal is that we don’t need new heroes, but rather an understanding of our past to face the complexities of contemporary times.

However, society continues looking for false leaders who tell us about solutions and structures that will never happen if the heroes who misuse power continue existing. Beyond the Berlin Biennale, how is it possible to tell people that we do not need these heroes, but ourselves?

Thiago de Paula Souza: First, I don’t know! The exhibition is only possible because it happened here in Berlin. Even if the exhibition were to be produced with the same curatorial team in Sao Paulo, New York City, or Johannesburg, we’d need to find different ways to discuss what we wanted to discuss.

We came up with the title of the show “We don’t need another hero” because we can see how certain situations we are facing now in the contemporary moment were not resolved in the past. The way we see the discussion regarding the postcolonial legacy would not have been possible in another place. I’m not saying that the discussion wouldn’t happen, it would just be a different one. I’ve never been in Chile, but I’m sure that we’d talk about the history and its reading in other ways.

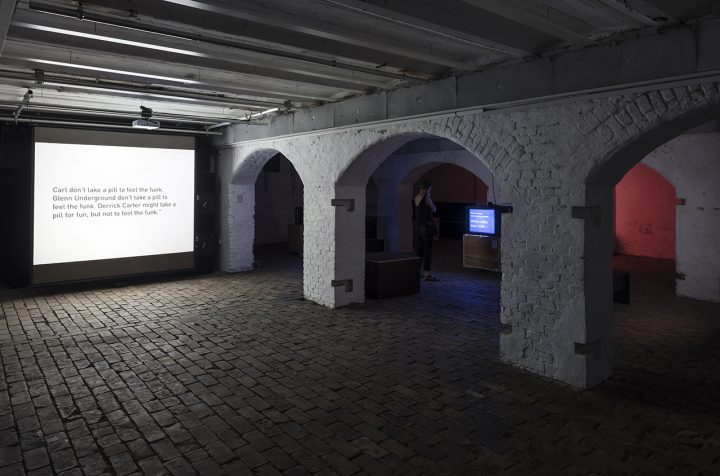

Within the scope of the curatorial practice, one can understand exhibitions as a way to communicate. Exhibitions can be a possibility to bring certain narratives and ideas across, never aiming to teach people anything. I don’t have this kind of idea that art should lecture you, but I do believe art allows you to come in contact with certain structures or discussions. The exhibition was a moment of pause when you could think about certain things and that is what we wanted to do with the Berlin Biennale.

“Within the scope of the curatorial practice, one can understand exhibitions as a way to communicate. Exhibitions can be a possibility to bring certain narratives and ideas across, never aiming to teach people anything.”

When I was in Sao Paulo working with Museu Afro Brasil (Museum Afro Brazil), we were discussing the legacy of Black people in Brazilian art history. I was working as an educator there, my position was quite different because I was dealing directly with audiences—which I cannot properly do here—and I was dealing with children in addition, so, the dialogue was different. It was an exercise in making people aware of the very small details in the violent Brazilian racial structure. There was really a discourse through the art or objects, but that was what the job demanded of me. Here at the Biennale, we really tried to find a new grammar to talk about certain things, maybe the same things imagining what the other possibilities are. When you read the curatorial text or the conversations, you see that we also tried to avoid certain words and topics; for example, we never use the terms colonial or postcolonial, especially because when the curatorial team was announced, people were sure that the exhibition would be the most political and most postcolonial exhibition ever. When people saw who formed the curatorial team, they immediately imagined a postcolonial curatorship.

“When the curatorial team was announced, people were sure that the exhibition would be the most political and most postcolonial exhibition ever.”

So, part of the concept was how to free ourselves how not to get trapped, because it would have been very easy to make “ a very postcolonial exhibition”. So, I think our greatest challenge was to try to not get trapped in the way certain people understand our subjectivities, not to make our lives a theme. So, yes, it has been an exercise in how to free ourselves, how to discuss certain things in a certain way, and also how to make people or white people understand the exhibition as an invitation for dialogue. As Gabi Ngcobo said before, we are all postcolonial, but sometimes certain people have to carry a certain burden. But this is not our job, as we said before we are not here to fix the mass. From the beginning, our exercise was to imagine how it is possible to go beyond certain vocabularies and certain levels. And of course the discussions regarding race, gender, equality, colonization, and decolonization are there somehow, but we are really looking for a more reflexive way. It is really tricky, but well, anyway, the exhibition is really about time.

CM: The theme of the African Diaspora is evident in the Biennale and could even be considered the starting point. It is interesting and impressive to see how the phenomenon of decolonization in Africa – its process and structures – is comparable with that of Latin America where national liberation occurred earlier. Speaking as a Latin American -without African roots, such as Brazilians or Cubans- I can see how a distance between the Anglo-Saxon world and us still exists. In the terms of Luis Camnitzer, the dialectic between mainstream and periphery – the racial violence on those who were oppressed and that it still happens today in different levels and layers. Although the curators of the Biennale are from places with this heritage, it is the white world that is now putting this history and phenomena on the map. What is the most suitable process for displaying an exhibition in that place, telling the story of others, but in a certain way within their domains of approval? What about that other colonized people in other parts of the world, oppressed and violated by Latin Europe?

TDPS: I think there is a misunderstanding about the 10th Berlin Biennale because the starting point was not the African Diaspora. We’ve never said that. It’s again how the media, press, and others imagined the exhibition, just because of who we are – and these assumptions just like the one you brought in the question tell more about you them about us. No one ever brought up these things with the 9th edition, which was curated by a group of white people from New York. Gabi mentions this statement from Toni Morrison in our curatorial conversations: racism keeps you from doing your job. It keeps you explaining yourself all the time, so you are so busy that you never can really do your work. So, it is not about the African Diaspora, but of course, we are a part of this African Diaspora somehow, but this is me, I come from Brazil, I’m black Brazilian. So, this Diaspora is far from who you are. It is like producing a text as a woman and understanding this text from the point that you are a woman, and yes, this is part of the subjectivities.

A white man has the freedom to do whatever he wants and his work and most of the time his work won’t be discussed, as in, “You are a white man, so, you did this exhibition”. It is very important to remark that.

“It is not about the African Diaspora, but of course, we are a part of this African Diaspora somehow, but this is me, I come from Brazil, I’m black Brazilian. So, this Diaspora is far from who you are. It is like producing a text as a woman and understanding this text from the point that you are a woman, and yes, this is part of the subjectivities.”

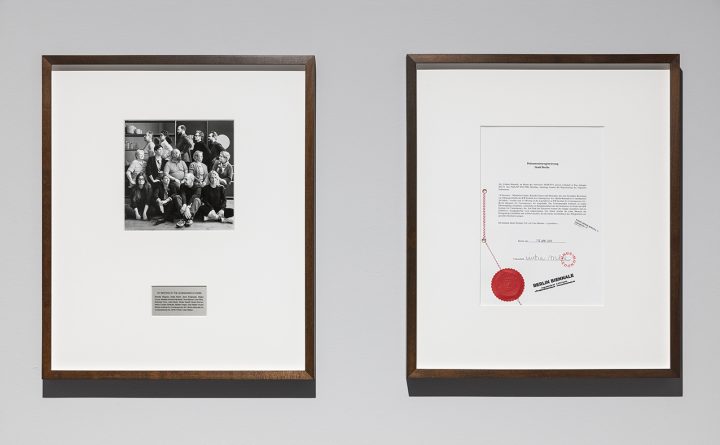

And on the other side, we are not telling the stories of others, because some of them are also our stories, but as I said, we are not making our lives a theme. For example, the work Legendaries by Cinthia Marcelle at KW Institute for Contemporary Art is inspired by a portrait taken in NY in 1942 at Peggy Guggenheim’s house where you can see fourteen European artists who escaped from Europe because of the war. It is basically a work featuring refugees, but we think about those people we don’t see them as refugees nowadays this word is only directed to people coming from a certain geography don’t use this word to describe it. So, it is interesting to imagine the changes, layers. This work was the starting point of the KW exhibition. She has produced others before in institutions both in São Paulo and Rio always inspired by this portrait.

With this work, we learned a lot about KW’s history, about the people who have worked in the institution that it is now. You see fourteen people and wonder who they are. That’s the portrait of the institution in those years, and maybe you can wonder about how important these individuals were, but maybe can even consider why there are no any people of colour there when Germany is a quite mixed country, although one might think it is not.—a lot of Turkish or Asian presence, for example (KW was founded in 1996). But going through the archives we also learned that there was a certain kind of social mobility in that hierarchical structure while when you see Marcelle’s version of the work in Brazil, of course, there are often black people, but they are always in the same position, I mean they started as doormen nothing has changed in twenty years. This project is really important for us because it helped to us to understand a bit of the history of KW, which is super important for Berlin, and in a certain way, to find analogies in different situations like Sao Paulo, Berlin, or Rio. And this project is very important for us of course, even though most people don’t even realize this project is part of the exhibition.

Regarding the most suitable or correct way, it depends a lot on if is a collective or a solo show, etc. But colonization is colonization everywhere, and abuse of power is always abuse of power. In this exhibition there is no geographic focus. We are not focusing on the decolonization of Africa or any specific place; we are trying to discuss things as power structures and of course, certain others ideas might follow One of the venues was Akademie der Künste, which is one of the oldest institutions in Europe. For a long time, it was an academy based on membership: a group of white European men decided who could be part of the Akademie. And because of that, it was very important to choose this venue and to invite certain artists that wouldn’t have been allowed there before: this is the exercise. It is not about demography or geography.

“Colonization is colonization everywhere, and abuse of power is always abuse of power.”

CM: In addition to being a member of the curatorial team, you were in charge of the public program “I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not”, a program that started a year ago in several places, both in Berlin and in other cities such as Johannesburg. This title calls for breaking down prejudices, challenging these historical processes that so many cultural walls have built. Tell me about your first vision of the program when it began in 2017 and how it was developed through this year.

We started “I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not” last summer ( 2017) when all the curators were here together in Berlin, making decisions about the artists we’d invite and thinking about the venues. We started in Berlin, and we decided to start in a place called Each One Teach One (EOTO), which is a cultural center and a library. It was interesting to start with them because it was a way to position ourselves as well, and it interesting to open the conversation because there are a lot of traumas in Germany. The African and German stories are not obvious stories for a lot of people who are not familiar with German history and the context. I hadn’t really been thinking about black people in Germany, for example. We learned a lot from that group, and they all have this interesting process to work to try to develop all these stories. Black people have been in Germany for a while but many people never think about this. So, the library and the activities in the cultural center try to organize all these narratives. Also, it is about addressing certain issues.

So, this group in Berlin is trying to tell all these stories and narratives about the black presence in Germany and now when the exhibition was already open, we have a series of events happening weekly.

“The African and German stories are not obvious stories for a lot of people who are not familiar with German history and the context. I hadn’t really been thinking about black people in Germany, for example. We learned a lot from that group, and they all have this interesting process to work to try to develop all these stories.”

During the same summer, we also met with the people from *foundationClass who also joined our program this year with a powerful performance reminding us that decolonization cannot be a metaphor. Well, the program is a way to embrace or discuss certain things that the exhibition is not able to do. We had screenings, talks, lectures, and performances. And the title, a double negation, makes some fun of what people expected that we should do.

CM: A public program of an art event like this one seeks to mediate, reflect and dialogue around the topics of the exhibition, through other actions or exhibitions. “I’m Not Who You Think I’m Not” has done screening projections, talks, etc. I think of a reality as distant as some cities in my country, Chile, where mediation or public programs must start from the most basic concepts of contemporary art, the most rudimentary stone for being able to at least, touch the problems that are involved. But at the same time, being so far away, we are living through immigration flows that have never seen before. It is urgent to take action on this from different areas, where art is undoubtedly one of the greatest “tools” of transformation and communication.

How do you divide the audiences in the program? What do you expect to happen to them? What is the importance of this type of programs not only for the artistic event within which they are framed but also for the society where they take place?

TDPS: I don’t divide the audience. I mostly don’t work with an audience in mind. We want to communicate but we can’t expect anything—this would be a very problematic attitude from us. What we really want to do here with the Biennale is open up the dialogue. And we organized the program as an invitation to open up the conversation. Chile is very different, because, for example, the Biennial in Sao Paulo has a very big structure in the mediation program. Museu Afro Brasil as well. it is about different realities.

CM: I guess that many of the assistants to the Berlin Biennale are part of the intellectual, political and economic bourgeoisie – heirs of the oppression of imperialism. And that even their interests are still divided between capitalism and socialism. How is it possible to build such a big project with these issues, taking a large part of them, either as spectators or supporters? How do you dialogue with this sector?

TDPS: The institution itself is a white institution, and it was also an issue for us to try to position to ourselves. What does it mean to have a group of black curators if the institution is so white? What will happen to the issues that we are discussing now when we leave? My contract will finish in October. What will happen to these discussions, will they become less trendy or fashionable? So, I’m really interested in how our presence will affect the future of the institution.

CM: After the 10th Berlin Biennale, what will happen with these issues, with Africa and the post-colonial project? I think many times the distrust for this type of subjects and curatorial concepts comes because once the event is over, the people and the topics are forgotten. How do you see the continuity of what this last version of the Biennial has done with the community and the world?

It is about time. I can’t really say now what will happen but of course, certain things change. It is something that we have to deal with our entire lives—it is a lifetime exercise. The visual arts world is quite small and I’m a foreigner, so, I really don’t know how this has affected people lives. Although sometimes it affects more than what people imagine. The exhibition was everywhere, in the newspapers, television, etc, so maybe it affected people in a certain way, but we still need to find a new way to talk about this. We can’t be surprised because a black group curated an exhibition – or at least you should not. Or when you see black curators, you shouldn’t immediately imagine that the exhibition is going to be very political or postcolonial, because that is racist. It is as violent as if you offend someone. I really hope that our concept of the exhibition has been unfolded and makes people take a look at these misconceptions, and reflect. Maybe in two biennials, there will again be a black curatorial team and I hope it is not a surprise. So we manage to break a bit of these misconceptions. I just hope so, let’s see.

“What does it mean to have a group of black curators if the institution is so white? What will happen to the issues that we are discussing now when we leave? My contract will finish in October. What will happen to these discussions, will they become less trendy or fashionable?”

Español

Español