The Chilean visual and multimedia artist Gianfranco Foschino is currently exhibiting “SED”, his fourth solo show in the country, at Centro Cultural Matucana 100.

This exhibition is about water and the different implications that this vital element has on the lives persons and societies, where through pieces of high observational character within specific time frames, travel from its different physical states to how the change in them can be derived from global political situations.

About the show, how art can make us aware of the climate crisis and the importance of dealing with these issues in Latin America and the world, is that we spoke to Dan Cameron, curator of the exhibition.

By Carolina Martínez | Images courtesy the artist | Photography: Luis Sergio

Carolina Martínez: How do you know each other with Gianfranco Foschino. What was the starting point to work together?

Dan Cameron: I’ve known Gianfranco’s work since seeing a video of his at the Biennale di Venezia in 2011. A couple of years after that chance encounter, I was collaborating with Sebastian Preece and mentioned that I couldn’t quite shake that video from memory, and he told me Gianfranco was a friend of his. We finally met in person at the SITE Santa Fe Biennial a year after that, and probably our first starting point for working together was the discussions we had right away concerning Chiloé, and the prospector making an exhibition there.

CM: Since some time ago you have been related to Latin America. What have you seen in this area that brings you here?

DC: I have a theory that one of the ways colonialism still manifests itself through the descendants of its former subjects in the New World is through an innate tendency to think of Europe as a focus point for all of our ideas about art and culture, rather than simply interacting with each other. This is particularly true in the way curators from the U.S. just can’t wait until their next trip to Europe, but they get all squeamish when they’re told they might want to travel to Ecuador or Brazil or Chile for the same reason. So if you go back in time to 1991, when I had 40,000 frequent flyer miles saved with PanAm, which was about to disappear, and I was planning my first trip to South America, I decided to visit Chile in part because it was the country that seemed the most difficult to obtain information about, although as a New Yorker, getting a list of names of artists to call once I got to Santiago was incredibly easy. I should also explain that as a US citizen, I’ve always felt a particular shared responsibility for the 1973 coup that overthrew Salvador Allende, not just for the social catastrophe that followed, but because it seemed to violate all of our stated principles about democracy, in particular the fundamental right of people everywhere to select their own form of government. So for years, I think I’d nurtured this naive, intuitive sense that one tiny way to make up to Chile for my government having destroyed its government is simply by paying attention to it.

CM: Why is especially important that a Latin-American artist deals with these subjects, that in a certain way are very global. How would you relate the global/local link regarding this?

DC: Latin American artists are in a very advantageous position, if you look at the question from a longer time frame. Yes, there are definitely hardships to living in societies where there isn’t a developed market for new art, and where access to the public almost always requires access to pre-existing modes of cultural patronage. And yes, it’s undeniably tempting to consider the material rewards that might accrue to that handful of highly successful artists who manage their blue-chip careers from global centers like New York, Berlin or London. But all markets are volatile, and previous recessions within the art market have tended to ravage the blue-chip layers first, triggering a restructuring of priorities that end up rewarding those who’ve toughed it out at the margins during the years of greatest excess. This is pertinent today because the globalization of art is a very real phenomenon, and current museum tendencies — the new MoMA being a good place to start — suggest that scholarship is moving outward from the centers and towards the so-called peripheries, and that Latin American art is one of the areas in which there’s both enormous curiosity and a comparative absence of reliable information.

CM: It is evident that we are not in a climate change, we are suffering a crisis. But according to Bruno Latour in his book “Facing Gaia” if we would really believe in this, we would change our habits radically. But is not like that. How art could help to become people aware of this?

DC: There are innumerable ways that artists can contribute to our collective consciousness about how we are rapidly wreaking destruction on our planet, but I think that the biggest part of that question has to do with whether art can affect consciousness at all. I happen to believe it can, and profoundly so, but I don’t think that the solution here is to instrumentalize art to draw attention to questions of ecology per se, because the issue isn’t that we need better posters, or better internet memes. What we do need, and what art can help with, is to try and instill in people an abiding belief and constant awareness that their daily actions have consequences that impact the world either negatively or positively, and furthermore that people are in charge of their own behavior. So many of our daily rituals seem to reinforce a double state of learned helplessness: i.e., that we are not in control of our actions, and that other people’s fates do not have a direct impact on ours. Both are the results, I believe, of late-industrial capitalism and a Neo-liberal economy, and they are worsened by a pervasive anti-intellectual climate that stifles critical thinking across the full social spectrum. Art can assist by permitting us to perceive the world in new and unexpected ways, and to challenge outmoded world-views, but the very best it can do is show us a world that invites our active engagement.

“What we do need, and what art can help with, is to try and instill in people an abiding belief and constant awareness that their daily actions have consequences that impact the world either negatively or positively, and furthermore that people are in charge of their own behavior.”

CM: You visited Chile in the hardest moment since the end of the dictatorship. We are in a sort of revolution and social explosion. Many say that the climate crisis is one factor of this. What do you think?

DC: The climate crisis is part of everything. It’s not in a separate compartment by itself, and as an example of that I think that most Chileans are well aware of how some of the inequities enshrined in the old constitution have contributed directly to their current feelings of powerlessness regarding the most important natural treasures — water, copper, lithium — that the country possesses. That said, if we agree that nothing else in civilization can be considered secure or safe until the climate crisis is confronted, that should give those same people who are demonstrating for a truly representative democracy in Chile an extra incentive to keep pushing. There will come a tipping point when it will be too late to effect meaningful change, and I think that the young are emboldened by their shared conviction that time is running out.

CM: Tell me about “Thirst” (SED) : the design exhibition, the chosen pieces and what are the marks that connect them?

DC: From the beginning, Gianfranco wasn’t interested in just developing an overview of his videos, partly since he’s still a young artist and hasn’t produced that much work. He was, however, becoming increasingly alarmed by how various concurrent crises in Chile seemed to have water as their major concern, so we sat down one afternoon and had a short jam session writing down single words that relate to water: flood, drowning, drought, thirst, etc. Then we started talking about the individual concerns that were present in each of the works that were either completed or in process, and the more we talked about it, the more we closed in on the simple word “sed” as touching on all of those overlapping interests. From that moment, deciding on the works to be included was the easy part.

“The climate crisis is part of everything. It’s not in a separate compartment by itself, and as an example of that I think that most Chileans are well aware of how some of the inequities enshrined in the old constitution have contributed directly to their current feelings of powerlessness regarding the most important natural treasures — water, copper, lithium — that the country possesses.”

CM: What is the importance of the project “Centro de estudios del agua” in the exhibition? And how do you expect the participation of the speakers in the talks since they are not related to art?

DC: “Centro de estudios del agua” or CEA is sort of the other side of the coin, in the sense that if the videos in the exhibition speak to the parts of our brains that are more responsive to sensorial input, and respond best to intuition and pleasure, then CEA is about accumulating the different scientific, ecological and pedagogical perspectives and offering them as a kind of rotating smorgasbord of invited thinkers and producers. As conceived by Gianfranco and realized through the tireless efforts of Sebastian de la Fuente and others, CEA on any given day could be workshops, talks, films, panel discussions, and/or cabildos, but always there is this resource library which is open and accessible to everybody, and which often contains multiple copies of certain books or fanzines, so that readers can take them home and share with others.

CM: Beyond the design exhibition, how do you go beyond the representation of nature through the image? How the artist should deal with this paradoxical division or distance?

DC: The artist is always constrained by the physical limits of the venue in which the work is being presented, which in the case of Matucana 100 means that the vertical dimension of the space needs to be an active element in the design, or else it overshadows whatever happens below. That incorporation of the vertical dimension takes place quite naturally with Aurora, which is suspended in the air, and with Bellinghausen, which covers a massive section of the wall. These presentation modes introduce the possibility of the unexpected, which hopefully generates a sense of wonder on the viewer’s part. They aren’t simulations of nature so much as adaptations of the architecture to evoke nature’s dimensions or elusive spatial qualities. You can’t directly reproduce nature’s evocation of the sublime in art, but you can gesture towards it.

“These presentation modes introduce the possibility of the unexpected, which hopefully generates a sense of wonder on the viewer’s part. They aren’t simulations of nature so much as adaptations of the architecture to evoke nature’s dimensions or elusive spatial qualities.”

CM: It is said that an art piece should be finished by the viewer. He should complete a meaning according to his expectative horizons (Eco). How would you describe the itinerary at the exhibition?

DC: This exhibition intentionally avoids having an itinerary, in part because the first phase of visiting it should involve wandering around to get your bearings. You can start on either side of the entrance, and the first thing you notice is how dark the interior is. I think it’s human nature to wait for your eyes to adjust, but once viewers have a general sense of how big the space is and where the pieces are locating, then it’s a matter of gravitating naturally to the one that interests you most, and then progressing from that point by instinct. When I’ve brought people on visits through the exhibition, I’ve done so chronologically, but that’s because one of the narrative threads you can follow is how the most recently completed works fell quickly into the context of the show.

CM: How the poetic and visual elements regarding landscapes, nature, water and its cycle deal with special issues regarding laws for example? Meaning with this, in Chile the water is privatized.

DC: Whenever people tell me that water in Chile is privatized, I have a hard time even comprehending what that means. I can understand that bottled water is privately owned, but how does that apply to the water that comes out of your kitchen tap, or to the water in a river in Patagonia? If in the latter two cases, the rights to that water belong to a private entity making a profit from it, that seems hard to rationalize. In the U.S., the municipalities, counties, states, regional authorities and the federal government have distinct jurisdiction over the ponds, lakes, rivers, and coastal areas in their purview, and while there are also ponds and lakes with private owners, it’s not so common. My sense, in general, is that anything that is fundamentally necessary for people’s survival should not be privatized, and that the state’s stewardship of these resources should be closely monitored by the citizens.

CM: In your opinion, where is going this dramatic crisis. We will be able to face this? We will make radical changes in our daily lives?

DC: I learned a long time ago about Chile and political history that you collectively don’t have a very positive self-image when it comes to making big political decisions, and one doesn’t need to be a genius to understand why that’s the case. But setting aside the question of whether we’ll be able to sidestep making the planet uninhabitable for future generations since I don’t like to make predictions on such a grand scale, I believe that right now, Chileans mostly need to be reassured by their friends that, in this time of crisis, they are absolutely doing the right thing. What I witnessed last month during my three week visit to Chile was immensely inspiring, because it was clear on the faces of the young people demonstrating that they were determined to use whatever power they have to improve the world that they were brought into, and were not going to take “no” for an answer. Since we in the U.S. are in the midst of a constitutional crisis of our own and none of us know what the outcome of that struggle will be, it’s empowering to see the real social value of such determination and idealism in action.

Images

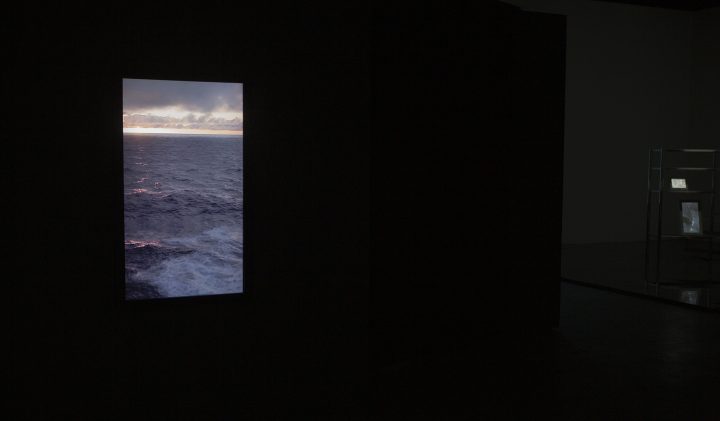

1. Still from Norwegian Sea, 2019. Video-installation: video, HD, 8 min., color, silent, loop.

2. Installation view, Norwegian Sea, 2019. Video-installation: video, HD, 8 min., color, silent, loop.

3. Still from Aurora, 2019. Rear-projection: HD, 12 min., color, silent, loop.

4. “SED”, installation view at Centro Cultural Matucana 100, 2019.

5. “SED”, installation view at Centro Cultural Matucana 100, 2019.

6. Installation view, Bellinghausen, 2019. Projection on wall: HD, 14 min., color, stereo, loop.

7. La Edad de la Tierra, detail, 2016. Six channels video-installation: video, HD, variable dimensions, color, silent, loop.

8. Still from La Edad de la Tierra, 2016. Six channels video-installation: video, HD, variable dimensions, color, silent, loop.

9. La Edad de la Tierra, installation view, 2016. Six channels video-installation: video, HD, variable dimensions, color, silent, loop.

10. La Edad de la Tierra, installation view, 2016. Six channels video-installation: video, HD, variable dimensions, color, silent, loop.

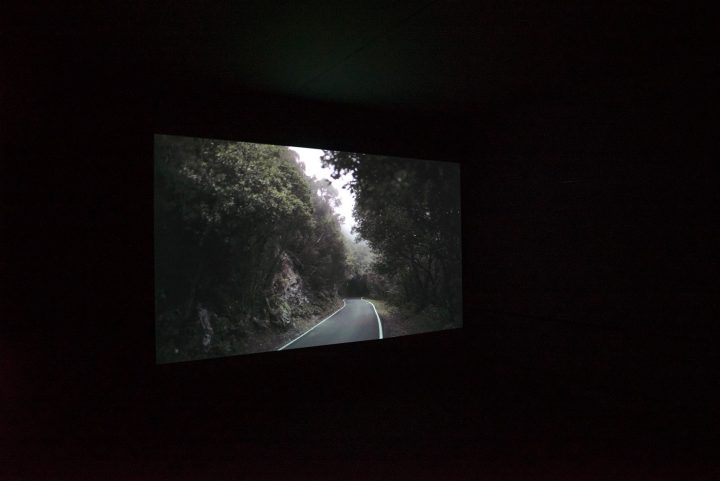

11. Still from Self-Motion, 2013. Video-installation: HD, 4 min., color, silent, loop.

12. Still from Self-Motion, 2013. Video-instalación: HD, 4 min., color, silent, loop.

13. Still from Espíritu Santo #2, 2013. Projection: HD, 5 min., color, silent, loop.

14. Espíritu Santo #2, installation view, 2013. Projection: HD, 5 min., color, silent, loop.

15. Still from Espíritu Santo #1, 2013. Projection: HD, 6 min., color, silent, loop.

16. Espíritu Santo #1, installation view, 2013. Projection: HD, 6 min., color, silent, loop.

17. Still from Villa Las Estrellas, 2019. Two channels video-installation: HD, 24 min., color, silent, loop.

18. Villa Las Estrellas, installation view, 2019. Two channels video-installation: HD, 24 min., color, silent, loop.

Español

Español