Robert Ryman is organized by Dia Art Foundation, curator Courtney J. Martin with the

assistance from Megan Holly Witko; coordinated at Museo Jumex by Begoña Hano | Images courtesy of Museo Jumex

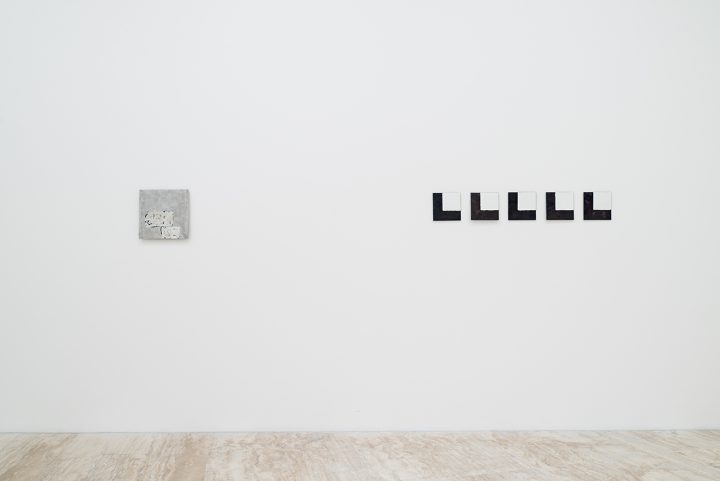

From March 4 to April 30, 2017, Museo Jumex will present a wide-ranging survey of the work of Robert Ryman. The exhibition, previously on view at Dia:Chelsea, brings together five decades of Ryman’s paintings from the 1950s through the 1990s. This is the artist’s first solo museum exhibition in Latin America.

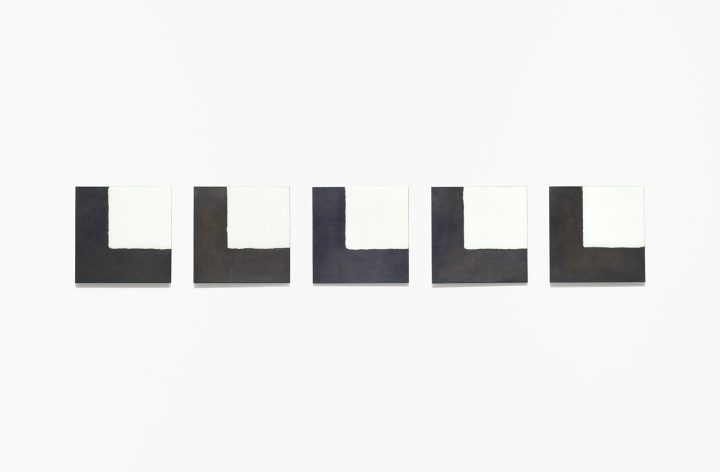

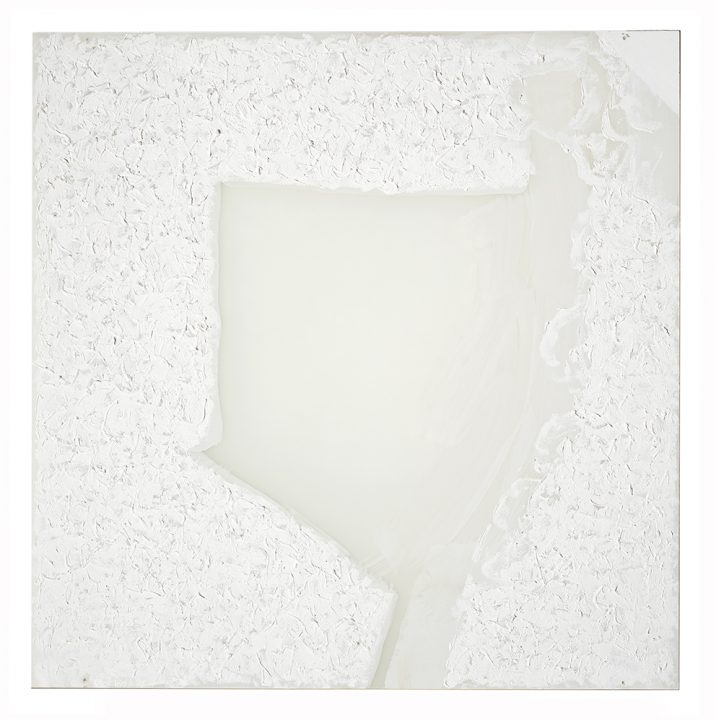

In this presentation, the color, material, method, structure, and style of twenty-four paintings reveal the remarkable experimentation of Ryman’s practice. Viewers see and experience these painted frequencies of light as the color white, but the artist’s exploration of the tonal values, luminescence, and spatial effects of white were never limited to paint. His early investigations into canvas, board, and paper expanded to include aluminum, Fiberglas, and Plexiglas, and evolved into a material vocabulary that is as revolutionary as his use of various white hues. As such, Ryman’s works are often discussed in relation to Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and Postminimalism.

Correspondingly, the notion of “painting” is extended to three-dimensional works, where the materiality of the support surface is displayed as part of an uninterrupted interaction with the gallery architecture. The exhibition at Museo Jumex highlights Ryman’s signature innovations, including one of his first paintings with fasteners, paintings on aluminum, and a painting in baked porcelain on copper panels.

ROBERT RYMAN’S LIGHT

By Courtney J. Martin

“Light is extremely important, how it’s shown on the painting and whether it comes from the front or from the side and whether it’s a soft light or a bright light. It all activates with real light.” [1]

In discussions of his paintings, Robert Ryman often references something that he calls “real light.” Real light is the way in which paint reflects the natural or artificial light of its surroundings, as well as the ways in which paint absorbs and refracts light when applied to different surfaces, such as aluminum, board, canvas, paper, and plastic. Ryman also defines real light a third way: it activates painting. Though he has long painted in the artificial light of his studio, he prefers to show his work in daylight so that the varying degrees of natural light—low to high, sunny and bright to dim and blue-gray—illuminate various aspects of the work. It is as if the change of light throughout the days and seasons allows his paintings to “take on a different life” with each new cast. [2] Luminescence is a consideration from the beginning of his process, starting with the kind of paint used and methods of application to specific surfaces, through to the end, affecting the way in which the paintings are displayed.

While always a part of the work, the importance of light for Ryman has not always been apparent. Since the 1950s, his paintings have been both readily identified and identifiable by their achromatic surfaces, ones that transmit light without separating it into visible colors. As viewers, we experience these painted frequencies of light as white. Ryman’s early paintings include studies that examine how white, frequently perceived to be the absence of color, is in fact composed of multi-color tonal gradations. Untitled #17 (1958) is such a painting. Despite the seeming whiteness of this work, a thin black line runs along its right side, marking a space between the densely layered paint to its left and the thinly applied paint to its right, visually prohibiting the spread of pigment across the canvas. When closely examining that line, other colors lurking beneath the surface become visible—small flecks of dark orange, red, and yellow with large streaks of gray and black that are broken by layers of off-white. The dense paint is both exacting and commanding.

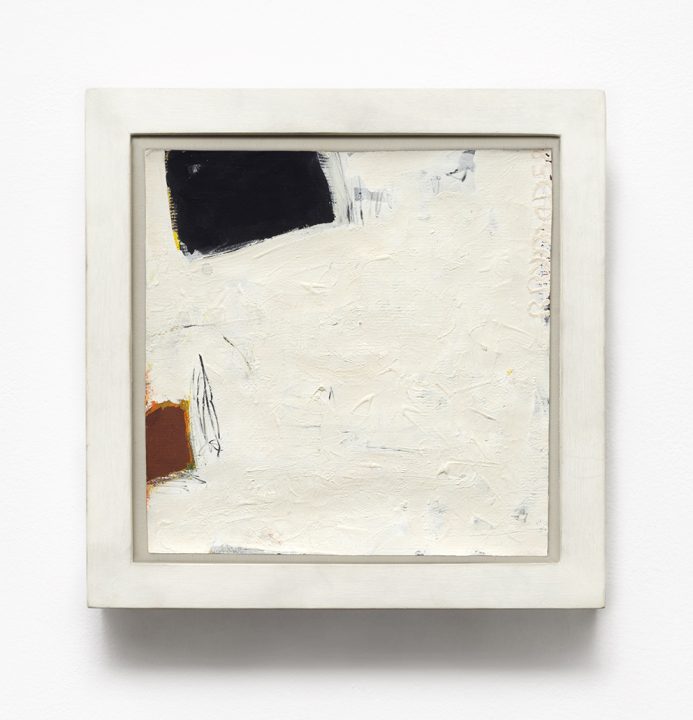

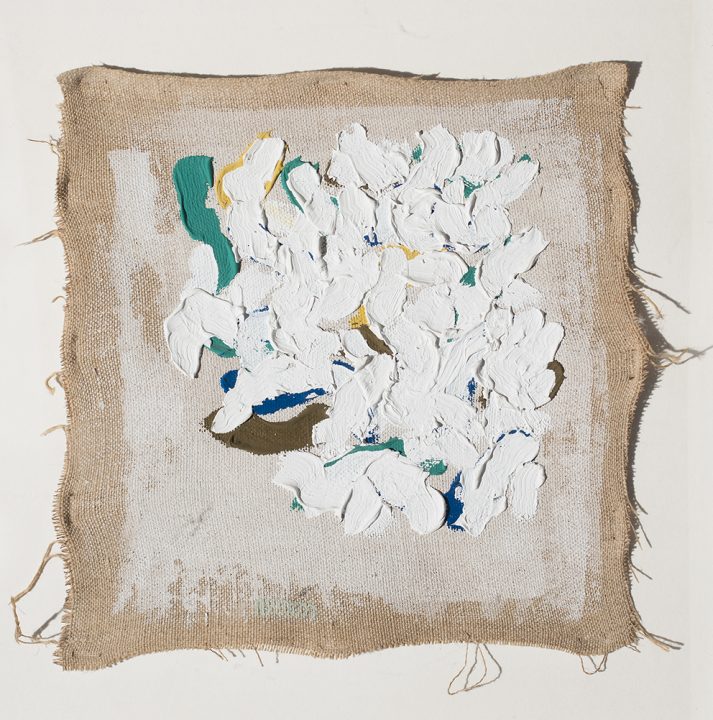

Deeply aware of his materials and their abilities, Ryman has described his aesthetic practice as a “challenge” to “make something happen” with white paint. [3] Similar to many of his early works, Untitled #17 was likely achieved by first “putting down a lot of color” and then “painting out the painting” with white. [4] This method of overpainting color with white is one that Ryman saw not as adding white paint so much as “subtracting” to let the underlying color inform the surface. The process of subtracting left traces of “a little red here or a blue shape slightly on the edge” that could then pick up and transmit the natural light in which the completed work was shown. [5] Untitled (1958) is another early example of how Ryman approached color to create his compositions. In this work, two semi-square wedges of color—one black painted over yellow, the other a rust brown painted over a sunny orange—emerge from the top and left sides within a field of white marked by sgraffito scribbles, lines, and spurts. His color choices in this work on paper reflect some of his earliest interests in art. While working as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York from 1953 to 1960, he carefully studied the palettes of noted colorists like Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Mark Rothko. [6] Many of Ryman’s works showcase dramatic tonal contrasts set off by expressive brushwork. Alternating thick swaths of pigment with thin layers of primer, his marks reach the edge of the canvas in order to realize the shape of the square. Completed a few years later, the colors (blue, green, gold, and maroonbrown) in 8-1/2” Square (ca. 1962) peak out from underneath the heavy, short white strokes that overlay a thinly applied gesso square. That square shadows the shape of the unstretched canvas and brings attention to the variance in tonality and viscosity of the different types of white (gesso and oil) as well as the other colors. [7] Painted in the same year as both Untitled and Untitled #17, To Gertrud Mellon (1958) was the only painting that Ryman displayed in a 1958 MoMA staff exhibition. Gertrud A. Mellon, a noted patron of the arts and a member of the museum’s Painting and Sculpture Committee, purchased the work, which marked Ryman’s first sale. In 1990 Mellon returned the painting to Ryman, who then retitled it in her honor. The painting features a vertical rectangle of black paint over areas of green and white. Most of the marks made with graphite, paint, and pencil appear on the left side of the sheet, while the unpainted right side displays the ochrehued paper underneath. This painting also suggests the impact of those earlier painters that he had seen at MoMA.

His job at MoMA was the detour from music to painting that educated him in art history and was his introduction to other working artists. There he became friends with artists and critics—like Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, Lucy Lippard, and Robert Mangold—who would shape the first decade of his career. By the mid-1960s, Ryman was included in a number of group exhibitions that showed the development of his practice. One of these was Eleven Artists, which was organized by Flavin at the Kaymar Gallery in 1964. [8] Though installed for only two weeks, the show was an early example of how Ryman would later be compared to peers Jo Baer, LeWitt, and Frank Stella, as each engaged with the discourse of painting in the 1960s in very different ways. In 1966, Ryman was invited to participate in Systemic Painting at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Curated by Lawrence Alloway, this was Ryman’s first placement in a large-scale exhibition at a major museum. [9] This exhibition, which also included Baer, Mangold, and Stella, further established Ryman’s career by anointing him one of “the younger generation of abstract painters” in America.10 Ryman was given his first solo show at the Paul Bianchini Gallery in New York the following year. [11]

As his career grew both in the United States and internationally, he continued to experiment with supports. After creating many works on board, canvas, and paper, he transitioned to aluminum in order to experiment with the direction of light before the application of paint. Lightweight and soft, aluminum is a surprisingly durable metal, and its reflective quality made it ideal for enameling, working with oils, and, in the case of Untitled (ca. 1964), painting with vinyl polymer. Using aluminum as a ground, he enhanced the metal’s natural luminosity by burnishing it, relying on the shape of the square to balance the composition, and situating the work within an environment to better capture light. As other metal supports followed, Ryman became more experimental. For his first solo show in 1967, he introduced a serial painting on rolled steel and by 1973 he tried copper. When Ryman showed the baked enamel on copper serial paintings in 1973 at Ausstellungen bei Konrad Fischer in Dusseldorf, one critic described the composition’s enameled surface and copper support as being separated by “a light refracting shimmer.” [12] Ryman’s move into the metals by way of aluminum signaled his curiosity about industrial materials, which he continued to explore through acrylics, Fiberglas, and various hanging devices. Tape, specifically masking tape, is one of these varietals. Around 1967, Ryman affixed completed paintings on paper with masking tape to the wall. The tape and the paper proved to be symbiotic.

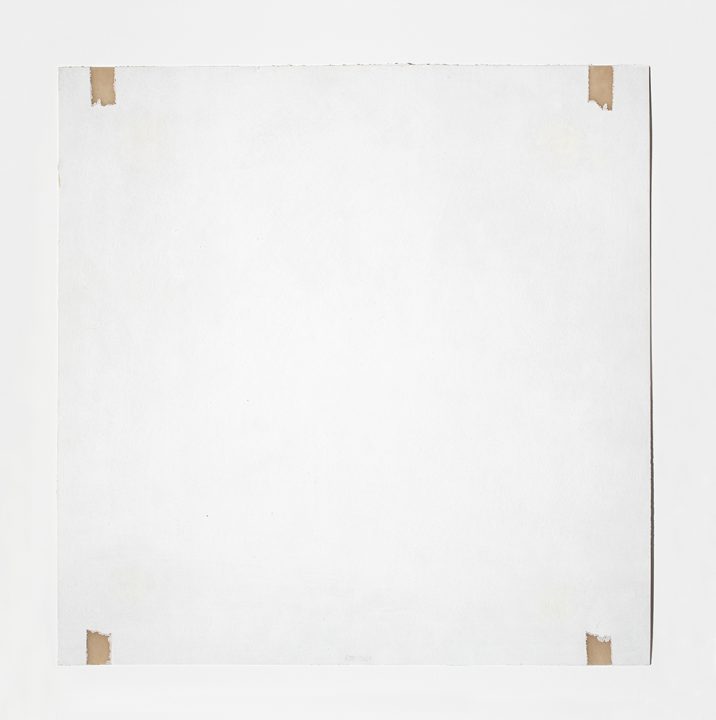

As a tool for display, the tape was roughly equal in thinness to the canvas that it supported. Later, he employed the tape in the painting process. First, he applied tape to the corners of a painting, then painted over it. Once dry, he then removed the painted-over-tape to reveal the negative space of where the tape had once been. In Untitled, Prototype (1969), the quasi-rectilinear outlines near each of the square’s four corners are darker in tone than the acrylic polymer visible on the rest of the painting. It is as if the composition was exposed to direct light in four concentrated spots (or conversely, that the rest of the composition was shielded from sunlight and allowed to retain its lighter hue). The “neutral vehicle” of the square ground is in dialogue with the active site of the less-than-perfect rectangles of removed tape. [13] In this work, the absence of the tape reveals the presence of the fiberglass ground and alerts the viewer to different temporal modalities in the painting: before, during, and after, as the tape was applied, painted over, and removed.

Ryman’s other hanging mechanisms have similar relationships to time. Arista (1968) is one of a few paintings in which Ryman stapled the canvas to the wall. A blue chalk line completely surrounds it. Over time as the chalk gradually disperses into the air, the line becomes fainter and less perfectly linear. The presence of the line and the staples makes one aware of the depth of the work and the wall onto which is hung. Classico 6, also from 1968, has a similar ability to engage an interaction between the surface and the wall on which is it hung. After first hanging sheets of the Classico brand paper to the wall with tape, Ryman painted them. From there, he removed the paper (and mounted each onto foamcore) to reconstruct the six sheets into a two-by-three rectilinear grid. Like Untitled, Prototype, small dark areas where the paper breaks through the paint reveal the places where the tape was once applied and removed. Together, the vertical sheets image a centered square painted on them. This square is enhanced by the shape of the whole painting from which a soft light seems to move from the dark edges toward the middle. The seeming rigidity of the paper is in direct connection to the stable wall on which it hangs at a slight remove.

Ryman’s transition from soft, pliable and more informal hanging devices like tape and staples to prominent hardware, bolts, screws, and so on occurred around 1976. One of his first works with visible hardware, Arrow (1976), features a square Plexiglas panel with four evenly placed Plexiglas fasteners (two above and two below) that attach the painting directly to the wall. At first Ryman commercially sourced his hardware, before having fasteners specially made for his paintings. Both serious and playful, Arrow was first shown in his 1977 solo exhibition at P.S. 1 (founded in 1971 as the Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Inc.) in Long Island City, New York. [14] In the same year, the hardware appeared in several works on view in his second retrospective, held at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London. [15] The added structural element suggests a kind of inner life of the painting and its relationship to the space around it. The fasteners communicate to viewers how they should be looking at and all around the painting and the wall on which it is hung. As the artist has remarked, his paintings “don’t really exist unless they’re on the wall as part of the wall, as part of the room.” [16] As integral aspects of the paintings, the fasteners (some with surface shine and others matte or dull in finish) are another method by which Ryman uses compositional elements to retain, direct and activate light. The fasteners also draw attention to the symmetry of the composition’s shape and reflect other advances in his practice from the late 1960s onward, such as the introduction of paintings in low relief, use of corrugated paper, and choice to paint directly on the wall. Taken as a whole, these innovations explain why Ryman—a painter adamant about his devotion to the practice and at ease within the matter of manufacturing, including new materials and fabrication—is sometimes aligned with both Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism.

His conception of real light is part of a greater anti-illusionistic concern, given his reliance on the veracity of his materials and method. The realness of light illuminates the color, material, method, structure, and style of his protean painting career.

I would like to thank Stephen Hoban, Publications Manager, Dia Art Foundation, and David Gray, Project Director, Robert Ryman Catalogue RaisonneÅL, for their kind and generous assistance in the preparation of this essay.

1 Robert Ryman and Urs Raussmüller, “A Painting is Basically a Miracle: A Public Conversation in the Garden of Inverleith House,” in Christel Sauer, ed. Robert Ryman at Inverleith House Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (Frauenfeld, Switzerland: Raussmüller Collection, 2006), p. 26.

2 Robert Ryman, interview by Gary Garrels, Robert Ryman (New York: Dia Art Foundation, 1988), p. 12.

3 Phyllis Tuchman, “An Interview with Robert Ryman,” Artforum 9, no. 9 (May 1971), p. 46.

4 Robert Ryman, interview by Paul Cummings, October 13 and November 7, 1972, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 For a longer discussion of Ryman’s use of the square, see Robert Storr, “Simple Gifts,” in Robert Ryman (London: Tate Gallery; New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1993), p. 17.

8 Eleven Artists. Kaymar Gallery, New York, March 31–April 14, 1964.

9 Systemic Painting was on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum from September to November, 1966.

10 Hilton Kramer, “Systemic Painting: An Art for Critics,” New York Times (September 18, 1966), p. D33.

11 Robert Ryman: Paintings. Paul Bianchini Gallery, New York, April 11–May 3, 1967.

12 Barbara Reise, “Robert Ryman: Unfinished I (Materials),” Studio International, 187, no. 964 (February 1974), p. 79.

13 Diane Waldman, “Introduction,” Robert Ryman (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1972), unpaginated.

14 Robert Ryman: Paintings 1976. P.S. 1, Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Long Island City, New York, January 26–February 20, 1977.

15 Robert Ryman. Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, September 21–October 23, 1977.

16 Barbaralee Diamonstein, Inside New York’s Art World (New York: Rizzoli, 1979), p. 334.

Español

Español