The Andrea Wolf’s obsession for the documentation comes from a very personal story. But the way our memory works and how our memories are configured, has led to the Chilean artist based in New York to create pieces that challenge and reframe the image within our actual visual regime. This interview is about the value of the image today, of how the new devices have changed our perception and the remembering way, and her last exhibition in Chile.

By Carolina Martínez Sánchez | Images: Josefina Lagos | Translation and special thanks to Jacob Sheehan

Carolina Martínez: Let’s start with the fact that you come from a background of journalism and social communication. When or how did you realize that you wanted to shift your focus towards visual communication, or more so towards an artistic manifestation, who faces the work is taken somewhere else other than the place of than that of the orthodox communicational phenomena?

Andrea Wolf: Studying journalism I realized that I didn’t want to be a journalist; I worked for magazines, radio stations, even television…almost everything related to journalism. It also happened to be a time when my group of friends and I wanted to make documentaries, and that’s where the first change arose: think of an elaborate product. The idea of telling stories and working with video was meant for me. For my last semester of university I studied abroad in Spain, which is where I found that the same university had a Masters program with a focus in documentary filmmaking, so after finishing my Bachelor in Chile, I went back to enroll in the program. It was then that I became fascinated with the classes and the theoretical aspect of the matter and truly exploded my brain with all of that information, learning so many things that I didn’t know about. From there, due to some “technological traumas”, I enrolled in a different program to receive a Master in Digital Art. Once free from those fears, I was able to understand the potential you’re given in the freedom to create your own tools. The moment to do my thesis had arrived, I decided to create a project titled, “memoryFrames” with Silvia Laura Carli, which was my first work, in which the user picks the memories of a leading, fictional protagonist. I think it was then that I began to elaborate the idea of a work reflecting the reality that our memories are interchangeable, and that make the function of my memories spin.

CM: Being an artist was something that arose when you finished your undergraduate studies, even with already having experience as a journalist under your belt. From there, how was the beginning of entering the art world for you?

AW: I think what made everything easier for me was the niche or community in relation to the arts and technology; it is true that it is becoming less new, but until a few years ago, it was still a novelty in Chile, besides the fact that this environment is extremely collaborative. This is the concept of “open source”, and in someway if felt among the communities. I went to Barcelona, followed by Boston, and when I came back to Chile, I returned to work in television already having the experience under my belt before leaving and I was supposed to return to that line of work, but I knew it wasn’t for me so I had to make a decision. By doing that, things just began to flow.

“I’m obsessed with the idea of catching time, of having a type of capsule that doesn’t let time pass without something tying you to it.”

CM: How is it that this near obsession for the act of documenting occurs in you? Would you say is first, the desire of approach to understand and execute documenting, or does it grow as you formally explore it through research?

AW: I think that they compliment each other, as well as there being a very personal history. My father died in an accident when I was a young girl, and when I began to grow up I realized that the memories I had of him were quite similar to those of what I saw in his photos. He filmed us, and no one else continued afterwards. Some time later, I found those videos and possibly without being so conscious, began my interest in those old recordings.

Then adding some theoretical issues that interested me, everything began to blend together. The topic of the representation of the image, what value we give to that representation versus the true worth. The same can be said for narratives and identity. But I didn’t like the idea of only working with my material, even though I sneak some autobiographical elements into it, it doesn’t play a principal role. With the project “memoryFrames”, I had already started with this idea and became accustomed to gather memories from other people, now being an obsession. In that sense I’m interested, how much worth we give to these objects of memories, what’s the value given towards the documentation.

That’s how the phrase in “Sans Soleil” by Chris Marker comes to mind, “We do not remember, the memory is rewritten just as history is rewritten“.

I’m obsessed with the idea of catching time, of having a type of capsule that doesn’t let time pass without something tying you to it. I find it very interesting the idea of memory as a narrative or action, as if it were something outside of us; as if every time we remembered, we created a new memory. Remembering from a very specific place. I’m interested in all of these areas and I like to investigate them from all these records. I do not know if you can truly make a hypothesis, but it is interesting to think that if the memories of others detonated our own memories for example. Which is the stereotype of “remembering” in Western society.

CM: Why should you let go of your memories and your experience?

AW: I see that my memories can exist in the memories of others, I recall things, and I become excited. I think what I try to do is speak anonymously from that extrapolation, where you can reach each person separately. If I work on it within myself, the issue would certainly be another, and I’m interested in the general idea, the intersections and parallels. I like thinking about the hypothesis that our memories are interchangeable. Does it actually matter if I’m the one who’s in the vacation photo? Is there a stereotype or cliché of the memories and the past was better than the present?

“I do not know if you can truly make a hypothesis, but it is interesting to think that if the memories of others detonated our own memories.”

CM: The name Harun Farocki and his documentaries come to mind, which are undoubtedly from a political and critical demonstration, that also try to explain how humans organize, distribute and manifest structures for living, based on the collective acceptance of “As You see” (Wie man sieht). The floating image of José Luis Brea comes to mind, where the digital image belongs to no one; it is an archive that belongs to all. I also think of Boris Groys or Hito Steyerl that say that the digital image has a place, from the moment that it’s recognizable and is given a name, even if the image is “poor”. What’s the fascinating thing about this digital image in a permanent conversation regarding nature? How do you implement these “thefts” or “image borrowing” and what’s your take on their nature?

AW: It’s interesting that in this moment, I begin with an analog image, which then due to technical issues is digitalized later that allows me to work on the object later. It’s also a sort of transition that’s personal: I grew up with the rolls of film that show the way someone thinks of memories and documentation. Now take the overpopulation of digital images, there’s an enormous level of production and distribution; everyone has an iPhone full of photos, on iCloud or Instagram. The discussion of the digital image is very interest and complex because analog images had a physical transference, there’s a chemical process that’s at work. In exchange, with the digital image everything becomes “opaque” although more democratic because most people don’t understand it well. As everything that happens in society nowadays, it’s all defined in the flow of things, with everyone in the dark. For example, it’s extremely difficult to visualize the sheer number of servers necessary to keep everything functioning. So this whole thing creates these conflicts for various reasons, take the conservation of images for example: there’s no physical wear and tear like that of an analog image, yet if you have a corrupt file you’ll never open it again. Or maybe, the uncertainty that at one point or another the hard drives you own won’t be readable. And at the same time we generate so much information that we often forget to revise it. The reminder photo gets confused for the “souvenir” photo; you go along making dynamic, varying and strange archives. That’s what happens with digital memory, it’s something to do with the obsession to document every moment, every instant, but not to go back in time later on in the future, if not to immediately share it in the present. It’s a continuous present. It’s not like all of the necessary and lapsed time between taking the photo and revealing it. You gave the space a name, “The Box”.

Now it’s about accumulating, accumulating, accumulating, share, share, and share. We don’t even go back to it later. This speaks of the relationship with digital images that’s there but isn’t there, besides the fact that it’s changing in this age of the super-spectacle. The way we relate to information today is due to these layers upon layers. Technology doesn’t interest me for the technology; I’m interested in the extent that it serves me to be able to tell something. Sometimes you get stuck in the pyrotechnics for the same, new recourses that are appearing but it doesn’t make sense that way.

For example, for the project in NEW INC together with Karolina Ziulkosky, we made a superimposition of layers, but also from the time. Two years ago, I found myself in Mexico in an antique fair with a newsreel from 1937 and on the front page there were five, current world leaders invoking and wishing their wisdom upon the readers, pre Second World War. But seeing the news today, you think about how we have (not) learned, how many times has everything been repeated. So what we did, was in parallel to the news from 1937, we alternated with today’s news. We recreated a living room from 1937; you could sit and view the newsreel with an iPhone, like augmented reality, going between the news. I’ve seen some works that in removing or placing the image that’s already there, you question the worth of the first image, of that first layer.

“The discussion of the digital image is very interest and complex because analog images had a physical transference, there’s a chemical process that’s at work. In exchange, with the digital image everything becomes “opaque” although more democratic because most people don’t understand it well.”

CM: You went from recording methods and older or “vintage” instruments, leading to an overall aesthetic result this nostalgia for such methods or instruments. I imagine that this was your first desire. But how can you reconcile the current processes and devices with this stage of your work? Wouldn’t there have been a gap in the conversation regarding our own ways to remember according to the postmodern processes?

AW: In my first works there was a bit less consciousness regarding how we remember today, there was a nostalgic idea of memory. I feel that when you remember, you’re doing in the texture of a Super 8 for example, there’s a thing of a visual language, of an esthetic to remember. For me it’s not just about the quality of the movie or with the objects. The truth is that it was natural; I didn’t think about it that much. I hope that with my work I can create experiences where memory is an action that’s super conditioned with a clear objective, and that we’re controlling it in each moment. That was my first approach, and I think that this dialogue between the old and the new always was interesting. The transition must have started with “Little Memories” I had this thing of leaving the gadgetry, even though it still remained physical. But there’s no doubt that the processes haven’t been that conscious. Although now I am (conscious) as well as being more aware of what it means to remember today.

On the other hand, the subject of the textures of the thousands of applications that exist is due to the old, and that’s what possibly gave it more weight and authority to an image of a telephone, I converted it into a document, but I think today we’ve liberated ourselves of that necessity to give it such status although many connections remain.

CM: At what point, and what is it that you wanted to start formally working on when you started to work with these unities and digital manifestations?

AW: I started with the subject of postcard and landscapes, and more than search for the digital unity, what I wanted to demonstrate was how much scenery like memory isn’t something external to us if not a production and creation, and for the same reason the discomposing of these images, where the sceneries transforms itself into much more abstract images, creates an experience; what do you see, maybe you take notice of a glitch or maybe not.

Bill Viola in a text speaks about hyper real images, and that’s what I feel. Sometimes that image is so real that it pulls you, that hyper sharpness and luminosity; the Super 8 has the warmest image. He said the search for the true image allows you to find it, but in the end it’s just and image. There’s no need to look for its intentional imitation. And I was stuck with this idea in my head of showing images that are only that, an image. To put it in these unities, is perhaps thinking of their true nature, the image being shown as an image. And that was a bit of the idea that led me to experiment with this work. It works based on the pixels it contains.

And that’s the intention, show the true nature of the image and not understand that the thing is itself, for the same reason we interpret it, there’s an experience, and from that experience come our memories and the idea of the place.

CM: Was “Weather has been nice” a way to open this new stadium of production and creation? Tell me about this project that is in a constant process, and how’s your next presentation in Chile being formed.

AW: It’s a project that’s in constant development. I don’t have any issues with revisiting the projects and the ideas to say to myself, “now it’ll continue like this”. They can be unfinished and could move towards another direction.

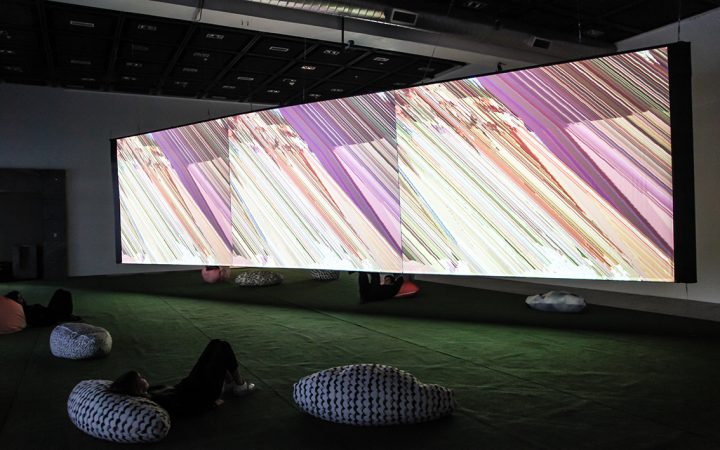

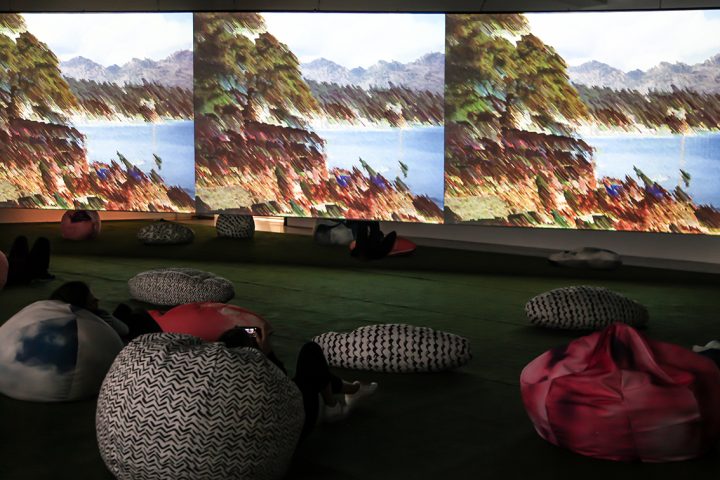

“Weather has been nice” begins with the idea of the image and its decomposition, and to develop the problem of how to present and arrange that image. I like to look for new ways and incorporate materiality. Moreover, what I’ve wanted to do for a while now was to incorporate the texts that are written on the back of postcards, since I only use postcards that actually have already been sent. I’m like a sort of Diogenes syndrome; each time I travel I look for these things. Having something written wasn’t only the souvenir of the store, but it’s a tangible memory of someone. For this exhibition, what I’ve decided to do is transcribe one hundred postcards in different languages, to later record distinct people reading them, that were grouped together and given to various musicians, artists and sound poets so as they were to compose something with the transcriptions. Each one of these recordings reside in each one of the seats or puffs that are in the installation, that way you can sit or lay back to see these images dissolving and transforming themselves, and at the same time you can listen to the audios of the postcards, so as each experience is completely different than the other. This show had its smaller first version in the showcase of NEW INC, with a wonderful reception, people hung around and installed themselves. It’s a space to stand and contemplate.

“And that’s the intention, show the true nature of the image and not understand what the thing in it is, for the same reason we interpret it, there’s an experience, and from that experience come our memories and the idea of the place.”

CM: Your approach to visual reflection regarding the saving, memory, production and reproduction isn’t only patentable in your work as an artist, but in REVERSE. How and when do you decide to undertake this project? What’s the way that it has adapted and how has it mutated? A bit of gallery, investigation, experimentation.

AW: Reverse started by accident. The idea of doing something like this was some sort of farfetched dream, that’s why I wasn’t actively looking to find it, but the spaces were what finally guided the choices. I was going through moving to a different house in that time, and in my search I found this place on the first floor, with the apartment sitting above on the second floor. I took it and rebuilt the place; everything was done freehand. It was a lot of work, but very enriching. Once I had the space I didn’t think much about it, and that’s how it started. I began with outsourcing, inviting curators to set up exhibitions, creating this editorial line where investigation and collaboration came into the picture. I grew whilst doing many different things.

But the moment comes when you have to decide. With the last show in September, I’ll close the project. It grew immensely, and in this moment it’s too much work to dedicate the time necessary to run a space and further my work. For me, now is the important time for my career, and reverse always was a large art project. Taking the decision was obviously something very important and decisive.

CM: After finishing your studies in Chile, you then studied in Europe, soon after heading to NYC. With that, can I think about the classic problem of isolation, of “low ceilings”, and the endogamic environment of art in Chile?

AW: When I went to Barcelona, I started with the idea of studying something that didn’t exist here. At the beginning when I returned to Chile it was hard for me, everything was strange for me. Maybe I wanted more of a challenge, and the possibilities are more restricted in the local context. Then I started to study again, extremely enthusiastic to learn new technologies. That’s how the Master of ITP was the only thing I wanted, being the only thing that I applied for, and was accepted. Going to New York was always with the idea of staying.

There’s also something else that’s very comfortable about living abroad; nobody knows you. When you’re searching for your vision to experiment, it’s easier to do it when there aren’t any menacing looks towards you. There’s something freeing about experimenting abroad, and I felt more comfortable doing it there. It was always something more personal rather than something that involves the system I don’t like saying that everything here is extremely dull. I think you can find your space and your own way of doing things. Today we’re so interconnected that everything is different and you can do it in all kinds of ways.

“When you’re searching for your vision to experiment, it’s easier to do it when there aren’t any menacing looks towards you.”

CM: Your exhibitions in Chile have been fading away with the years, even having had certain expositive highlights, AFA, Museum of Contemporary Art (MAC), etc, that to any artist it would’ve motivated them to persevere in the local context. How do you project yourself or in which state is your work today, and what do you hope to do with your work?

AW: In someway I’d like to maintain the link, but honestly speaking there isn’t much space to work with what I do. I don’t know if the galleries will be willing to show this, and in that sense it’s a bit more complicated. It’s not that in New York it’d be easier, but there are consolidated spaces that work with this type of work and esthetics, as well as initiative to “instill” digital art in the general public. Usually I always have expositions in the folder. Also, NEW INC has been a wonderful space, the New Museum backs it, where everything isn’t art; it’s also technology, design and investigation. It’s part of what interests me and what I do. I’m in a moment in which I’m feeling good doing my works. I’m working on a project with the slide files from the MET; the truth is that in this moment everything is flowing, and for the same reason in the minute I’d like to work in the things that interest me, and that’s what undoubtedly has to happen, like an antibody to that anxiety that you live day by day in NY.

CM: Besides your current project, today you have a non-profit project, REVERSE, and you’re a member of NEW INC, the division of the New Museum of NY that works like an incubator and laboratory for the cross between art, technology and new mediums. How is it that you got there and how is that experience working for you?

AW: It’s very interesting that a museum has created a space like this, where I enjoyed the idea of working with others. When you’re in your own workshop, sometimes you isolate yourself too much; working as we do there, you have a routine with people that inspire you and can show you other things. I applied to the program and I was accepted, I was there full-time during their latest season. This has pushed me with certain projects, to meet people with whom later on you will collaborate.

“Needless to say, although today there is more talk than ever of art and technology, the truth is that this intersection has always existed.”

CM: These tools that are serving contemporary art today seem to be one of the “trending topics”. We can see the same motion of the New Museum, Rhizome, even the last curatorship of the 9th Berlin Biennale, that was made by a magazine which works with these same intersections between art, critique, satire, fashion and technology. Is it truly where aesthetic and thoughtful expressions are heading? Or is it just one more of the edges of exploration in art today?

AW: Needless to say, although today there is more talk than ever of art and technology, the truth is that this intersection has always existed. I don’t think it’s the right way of seeing things to try to understand what’s happening. Undoubtedly it’s more massive and you can’t deny the fact that there are more people working with it and are increasingly implementing new forms of experimentation. It’s logical and is a natural evolution. It won’t replace the other forms of media or formats of making art. What I find interesting is what kind of imaginary and speech are being presented today. I find it interesting the effects that can produce this in the perception and representation of the world in different art mediums. And the new technologies are also a way to represent it, and sometimes more on par with what’s going on, because you can replicate the experiences.

“In memory, the function of the past isn’t a fixed unambiguous event, but the function of the past deals with desire.”

CM: I think of “Until the End of the World” by Wim Wenders, where the entire film focuses on the subsequent obsession to capture, record and archive our dreams. This is what happens in the audiovisual piece, but obviously with a logical deformation in its visual expression. Is the fascination for recording life as a whole and the best approach from another reality -virtual- to reality that is leading us in all paradigms? Art, science, technology, anthropology among others. For you, where does this obsession come from? Where do you want to go with it?

AW: There’s something of the “ideal”. In memory, the function of the past isn’t a fixed unambiguous event, but the function of the past deals with desire. All of the things that catch our attention and build up our identity, and all of the people that have investigated either from a scientific point of view or from humanities, is at the end of the day being guided by desire and not be seen from who we are. And when you understand it like that, I think the self-consciousness of remembering, how one remembers and how you’ve built your identity makes you know and see more. That can be applied to something personal and to society as a whole. It has to do with breaking the idea of the document as full proof of the larger picture versus the little story. At the end, desire, subjectivity and the present determine all of this.

Hopefully my work can create experiences where remembering is this super-conditioned action with a clear objective, that memory is an action and that we’re controlling it in every moment.

Español

Español