Regardless of this clash against reality, the title “Contemporary Diagram: Berlin” still suggests to me a social scan, rather than a scientific research. Can we as artists, as thinkers, somehow connect the water bacteria’s response to some kind of social behavior?

By Ana Rosa Ibáñez | Images courtesy Schering Stiftung and the artist | Photography by Roman März

How can science be considered an artistic practice? How can we think of art as a scientific process? Looking back at the history of the arts, we understand that it has always been there –even if at the moment itself it’s misunderstood– as a reflection of its society. Living today in an era where scientific research and technological developments are dictating social behavior, the coming-together of these two disciplines it’s a natural event, one that has resulted in an on-growing exploration of each other. On this base, projects of these natures are increasingly becoming an element of interest for both cultural and scientific institutions.

Berlin’s Schering Stiftung –to give an example– has been promoting the collaboration of life sciences and contemporary arts in Berlin since the year 2002. The curators Carsten Seiffarth and Markus Steffens from the nomadic gallery Singuhr Projekte, had already worked with them in the past, and this year decided to develop with them Cecilia Jonsson’s Contemporary Diagram: Berlin.

photo (1): Roman März // copyright: Roman März, Cecilia Jonsson, singuhr e.v.

photo (1): Roman März // copyright: Roman März, Cecilia Jonsson, singuhr e.v.

Singhur Projekte is a curatorial collective based in Berlin since 1996, and who have developed a large number of projects around the questioning of sound and space. Understanding sound as a medium for art (and not music) it’s a notion that has been developing as such only since the mid 20th century, gaining in depth and attention over the last decades. Considering the short life of this practice, Singuhr comes forward as one of the pioneer platforms and catalyzer of many sound installations and interventions in space, in a national level within Germany but also internationally due to their collaborations and residencies over the world. Between the years 1996 and 2013, Singuhr presented a total of 88 projects, that being only in the city of Berlin. Seiffarth (who declares not to have a taste for music) and Steffens have been mostly working with artists that explore how sound affects our perception of the material body, shapes societies and opens new possibilities for the understanding of reality, an invisible reality.

Art and science is not a familiar ground for Singuhr though. This initiative came from the artist Cecilia, who had spent the last few years trying to prove the alteration in the behavior of water bacteria (specifically the Ferro bacteria) if exposed to sounds. Seiffarth thought: Well, let’s just do it.

Through her work, Jonsson has been for long finding connections between the organic and the inorganic, making use of the scientific method and presenting it as self-contained artwork. Thus, it is the un-intervened observation and investigation of natural processes what becomes her thesis-project. The fine merge of the artistic approaches to questions of nature, and the use of a scientific aesthetic –isolating and organizing the objects of study–, questions the boundaries of the artist as scientist and vice versa; both acting as channels of unveiling human and natural behavior.

“Perhaps what we now see is a revival of the historical art/science partnership when the disciplines weren’t so clearly formulated and separated?”

photo (2): Roman März // copyright: Roman März, Cecilia Jonsson, singuhr e.v.

photo (2): Roman März // copyright: Roman März, Cecilia Jonsson, singuhr e.v.

“For me, it is important that art is connected to the world and, as an artist, I reflect what it is I am a part of. I am lucky to work without an underlying “gaining” agenda as result. I believe that “science” isn’t the only truth and that our senses, trial and failure, and the creative aspect of how we read and relate to the world often are put aside. Perhaps what we now see is a revival of the historical art/science partnership when the disciplines weren’t so clearly formulated and separated? I also find it interesting to follow the development of green technology, how studying the past can tell us something new of our future and further, how ancient knowledge and religious/mystic metaphors may be verified by the science of today. I believe in taking the time to observe, to step back to learn from other disciplines and the nature we are a part of.”

Jonsson’s approach to science has been largely influenced by the investigations and experiments of the Norwegian physicist Carl Anton Bjerknes, who researched the mechanical behavior of fluids. Not only in the experiments themselves, but also in the way the scientist notated his discoveries and ideas shaped deeply the direction of this specific project:

“An element that sticks out in the exhibition is the plaited paper strips with my own research notes. This idea derived from reading a biographical book of Bjerknes life written by his son Wilhelm Bjerknes. C.A. Bjerknes had troubles writing and he often had his wife or later a secretary to take notes on paper strips as he dictated his ideas and research findings. These notes he then used to pin to the wall, drawing lines between his discoveries to create new understandings. This method was actually how he came to his conclusions and it resonated very strongly to me since I don’t draw sketches, but write words and sentences in mishmash documents. I feel words are more open, free forms of becoming. It creates context, ideas, material, and foremost it can take new meaning depending on how you web it all together. Like a cycle, threads start to meet and communicate even if they weren’t connected from the start.”

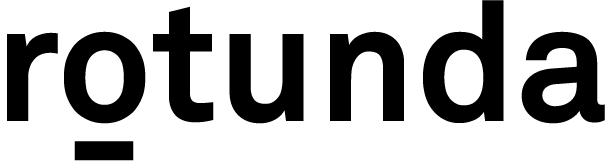

The exhibition intends from the beginning to immerse the visitor in a scientific environment; immediately at the beginning hangs a bottle of antibacterial liquid soap as if we were walking into a laboratory. Thoroughly displayed as investigation material, the elements used for the research (diverse speakers, books and bacteria samples) are presented underneath a glass vitrine. On the wall next to it, we faced the only installation of the exhibition: a map of Neukölln’s underground water pipes, slickly constructed with white nails and fishing string, against a (also white) wall.

The exhibition intends from the beginning to immerse the visitor in a scientific environment; immediately at the beginning hangs a bottle of antibacterial liquid soap as if we were walking into a laboratory.

photo (3): Roman März // copyright: Roman März, Cecilia Jonsson, singuhr e.v.

photo (3): Roman März // copyright: Roman März, Cecilia Jonsson, singuhr e.v.

photo (4): Roman März // copyright: Roman März, Cecilia Jonsson, singuhr e.v.

photo (4): Roman März // copyright: Roman März, Cecilia Jonsson, singuhr e.v.

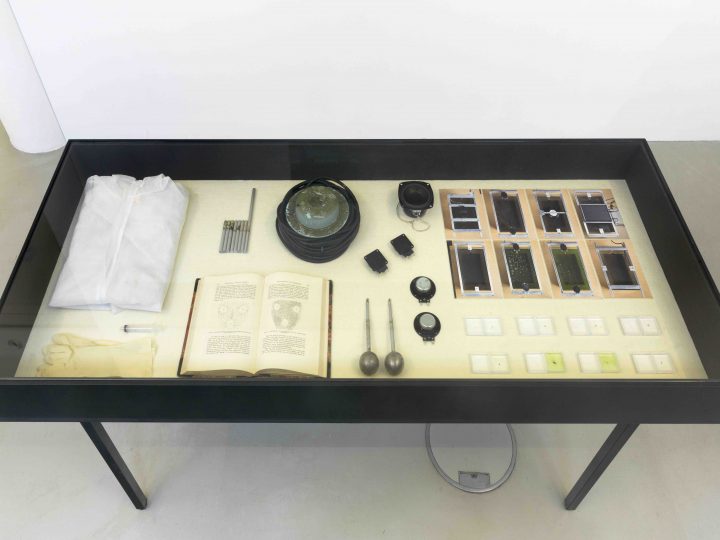

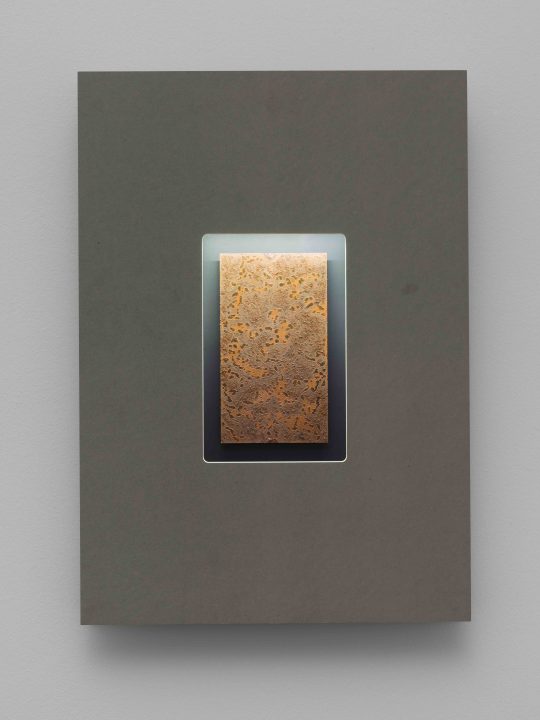

The biggest work of the exhibition is a series of cyanotypes showing the movement of the bacteria on glass plaques, and secondly –presented in a small space within the exhibition itself– the series of metal plaques on which the sounds were applied. The plaques were hanged in tanks during two weeks, each one with different sounds and through a variety of speakers.

Facing one of sound art’s biggest challenges –ephemerality– Singuhr and the artist decided to present the metal series to the audience contained in frames, behind which they mounted the speakers with the correspondent sound for the plaque. Some of these sounds are under the frequency that the human ear is able to perceive, but their presence in the show was necessary for the audience to connect the visual result to the process of the artist. The bacteria were exposed to a wide range of sounds, varying from Russian orchestra to Solfeggio frequencies. When inquired for the selection criteria, the artists described a somewhat intuitive process:

“Starting from the initial idea, and reading books of C.A. Bjerknes on life and hydrodynamic experiments of the mechanical behavior of fluids (that was visualized by iron filings); I became interested in taking the relationship between the “ocean” and “atmosphere” into a contemporary, site-specific setting with the inclusion and feedback of life forms. Like most of my works, the work/sounds I decided to use “webs” from different sources of information. Ideas that range from found research reports on bacteria/microbial corrosion/books/online sources, Ernst Chladni, living in the era of the Anthropocene and talking to microbiologists and different people around me. I was interested in exploring a broad scale of sounds/vibrations that start and end far beyond human perception of sounds (7.83Hz the Schumann resonance) and to use social/political (528Hz the miracle frequency) and other resonating links to the sewer (field recordings, 90000 kHz communication of rats, etc.).”

“Like most of my works, the work/sounds I decided to use “webs” from different sources of information. Ideas that range from found research reports on bacteria/microbial corrosion/books/online sources, Ernst Chladni, living in the era of the Anthropocene and talking to microbiologists and different people around me.”

photo (5): Roman März // copyright: Roman März, Cecilia Jonsson, singuhr e.v.

Reflecting on my own susceptibility to sonic stimulus, I immediately started to wonder whether the results from the metal plaques could point to some sort of organized reaction from the bacteria to the sounds. Can we identify in human reactions like stress or different types of flow? Seiffarth’s answer was clear: “No, not at all. You see that’s something different happening but definitely not enough for a scientific conclusion. There are always reactions. This plaque (img. 5), for example, was not exposed to any sounds, this is the result of silence, and you can see that is still very beautiful. The greener ones were the ones that had Led light on top in order to photograph the process, so the heat and the light created chlorophyll. The final thesis of the project is that bacteria avoid the area of the plaque that is vibrating because of the sound, that’s how they create these patterns.”

Regardless of this clash against reality, the title “Contemporary Diagram: Berlin” still suggests to me a social scan, rather than a scientific research. Can we as artists, as thinkers, somehow connect the water bacteria’s response to some kind of social behavior? Here is where I draw the line between these two disciplines, science being the one interested in the What It Is and art being occupied with the What It Could Be.

“Contemporary Diagram – Berlin has reference to Bjerknes experiment ‘Diagrammer’. Like I described first about the work, it’s a contemporary imprint of the sewer water and yes, like you describe, a social scan of a specific area in Berlin, in a specific moment of time. If the work had reproduced it would have generated a different outcome depending on where and when. I believe around 90% of the bacteria in the wastewater derives from the people living in the area and the bacteria culture is dependent on what we eat and do.”

Español

Español